How Hurricane Melissa was Impacted by Climate Change: Part 2

Part 2: Melissa in a Warmer World

Our discussion of the impact of climate change on Hurricane Melissa continues.

Now that we have discussed just a handful of features that made Melissa so striking, I want to move on to talking about how Melissa fits into the broader climate framework. The storm was located over some of the warmest ocean water on Earth, with sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) around 31° C, 1-2° C above average for that time of year [1]. Coupled with the deep thermocline in the Caribbean, it is undeniable that this played an immense role in Melissa’s intensification. The impact that climate change is having on the Earth’s oceans is generally well understood: over 90% of heat in the Earth’s climate system is sequestered in oceans [2]. Therefore, even though we cannot say that Hurricane Melissa was “caused” by climate change, it is reasonable to believe that climate warming may have assisted Melissa in becoming as strong as it did, since the maximum ceiling for the storm was made higher by warmer-than-normal SSTs. In addition, it is well-documented that the impacts from hurricanes will become worse in a warmer world: for example, higher SSTs cause more evaporation and increase the moisture content in the atmosphere, which causes heavier rainfall rates; rising sea levels from thermal expansion of seawater and melting continental ice contribute to coastal flooding and exacerbate the impacts from storm surge [3, 4]. One of Melissa’s worst hazards was felt several hundred miles away from the storm’s center in Hispañola, as the storm sat in generally the same area for multiple days and dropped excessive amounts of rain. It is quite likely that the amount of rain that fell from Melissa was made worse by climate change.

There is also the issue of slower-moving hurricanes, particularly in a warmer world. There is a documented trend that tropical cyclones, especially near land, are moving slower on average [5]. However, this finding is nuanced, and scientists still debate how much of this propensity is due to climate change versus natural variability. Kossin (2018, Nature) analyzed global tropical cyclones from 1949–2016 and found that the global average translation speed decreased ~10% over that period [5]. The link between warming and translation speed isn’t direct, but here’s a chain of reasoning that scientists have proposed> Hurricanes are steered by mid and upper-level winds in the atmosphere [5]. As the planet warms, the temperature gradient from the equator to the poles is decreasing, since polar regions are warming much more rapidly than tropical areas. This in turn reduces the strength of large-scale circulation patterns, such as the Hadley cell and the midlatitude westerlies, leading to weaker steering flows around tropical cyclones [5]. Indeed, Hurricane Melissa had incredibly weak steering currents in the Caribbean, which caused it to meander for days on end and drop abundant amounts of rainfall.

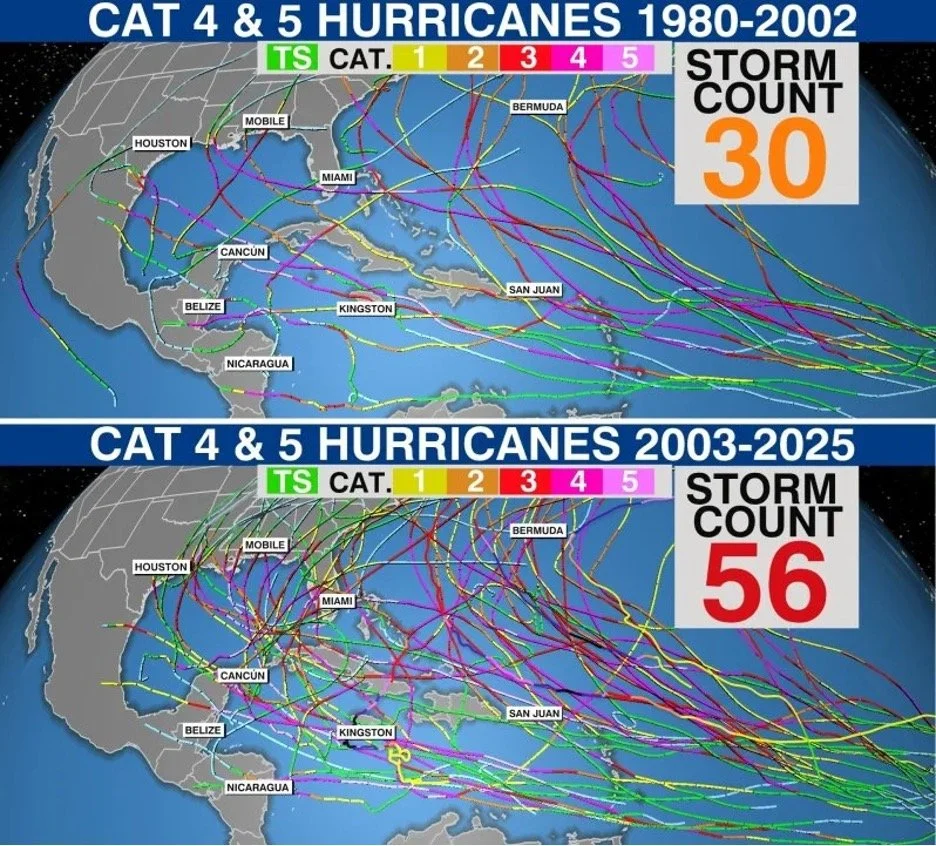

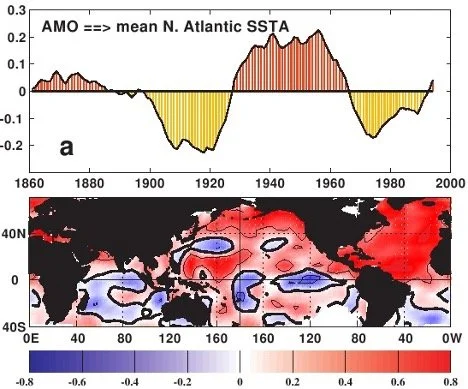

Therefore, while it is plausible and even likely that climate change made a storm like Melissa worse, there are still issues that exist when trying to attribute the system to climate change. In addition, some have noted that the number of category 4 and 5 hurricanes in the period 2003-2025 is nearly double that of 1980-2002, despite them being the same amount of time (see Figure 1). And while that may be true, we simply cannot draw conclusions about hurricanes based on 45 years of historical data. One reason this is problematic is that natural variability exists in the climate system in a variety of modes at different time scales. An important mode of atmospheric and oceanic variability is the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) [6]. As the name implies, AMO is a multidecadal oscillation with a period of roughly 60-80 years and it is defined by sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic [1] (see Figure 2) [6, 7]. The warm phase is associated with higher SSTs in the North Atlantic, while the cool phase is associated with lower SSTs. This variability is attributed to changes in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation [8, 9, 10]. Since 1995, the Atlantic has been in a warm phase that is considered the start of a “high activity area”, because the warmer SSTs have fueled more intense hurricanes. Before 1995 though, throughout much of the 1970s and 1980s, the Atlantic was in a cool phase, whereby SSTs were below-average across much of the basin and the Atlantic hurricane season was relatively quiet (of course there were still many powerful storms, but, on average, there was less activity than in a positive AMO setup). Warm and cool phases of the AMO have been documented even before the 1970s; for example, the 1930s and 1950s were a very active decade for Atlantic hurricanes when the Atlantic was also in a warm phase of the NAO [7]. Alternatively, some scientists suggest that the AMO actually reflects a change of anthropogenic aerosol emissions [11, 12].

Figure 1: Number of category 4 and 5 hurricanes for the periods 1980-2002 and 2003-2025. Graph originally created and posted by WFLA’s Chief Meteorologist and Climate Specialist Jeff Berardelli.

Figure 2: (Top) AMO index through time from 1860 to 2000 and (bottom) correlation between AMO index and SSTs. Figure borrowed from: https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/phod/d2m_shift/amo_fig.php

And herein lies one flaw of simply looking at the last 45 years of hurricanes from when satellite data become relatively reliable and consistent: from 1980 to 1995, the Atlantic was in a negative phase of the AMO, leading to below-average SSTs over much of the basin, which suppressed overall hurricane numbers [7]. Therefore, it is very difficult and irresponsible to say that the increase in activity seen in the 21st century is the result of climate change—we simply don’t have enough historical observations and there are too many confounding variables to draw that conclusion.

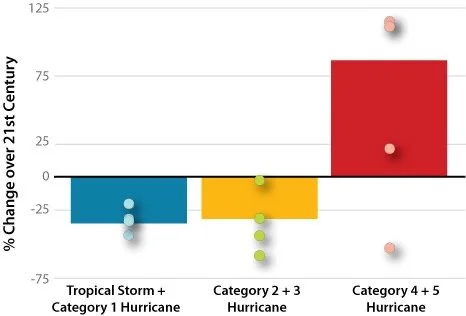

Another finding of which climate scientists are moderately confident is the projected increase in the number/proportion of more intense hurricanes (Category 4 and 5) in a warmer world [8]. Hurricane Melissa was the third Category 5 hurricane in 2025, quite an impressive feat given that 2025 has only produced 5 hurricanes in total thus far (below the 1991-2020 climatological average of 7) [13]. This is also the second most Category 5’s to form in a single season in the Atlantic, behind only the infamous 2005 season. 2025 is only one season and therefore we cannot say that the proportion of Category 5 hurricanes was made higher by climate warming; however, this does fit into the general expectation that we could see an increase in the percentage of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes forming, even if the overall number of hurricanes forming remains unchanged or even decreases (see Figures 4 and 5). But even here we must be careful, as any increase in Category 5 hurricanes especially may be partially the result of better observing systems (for example, more flights into hurricanes to more accurately measure winds).

Figure 3: Climate models project there will be fewer weak to moderate-strength Atlantic hurricanes as surface temperatures rise this century. However, the models predict that a greater number of the hurricanes that do form will tend to strengthen to category 4 and 5 hurricanes. The bars in this graph show the average results from 18 different models. The dots on each bar show a range of results from 4 of the 18 different models. Graph courtesy of Gabriel Vecchi, NOAA GFDL. Figure borrowed from: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/features/will-hurricanes-change-world-warms

Figure 4: Models project there will be an increase in hurricane intensities as the climate warms over the course of this century. Though there could be fewer Atlantic hurricanes overall, wind speeds for the ones that do form will be about 4 percent stronger for every 1°C increase in sea surface temperature. Graph courtesy of Tom Knutson, NOAA GFDL. Figure borrowed from: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/features/will-hurricanes-change-world-warms

It goes without saying that the impact of climate change on hurricanes is a tricky science, and research is actively ongoing. There are certain findings of which we can be quite confident, such as that the impacts from hurricanes are worsening and will continue to get worse with future warming [4, 5]. Other findings, such as the projected increase in Category 4 and 5 hurricanes in a warmer world, we are moderately confident in [8]. But when it comes to looking at history and saying that the number of powerful hurricanes has certainly gone up due to climate change, or that a particular storm was caused by climate change, our confidence is much lower.

References

2. https://science.nasa.gov/earth/explore/the-ocean-and-climate-change/

3. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/built-environment/articles/10.3389/fbuil.2020.588049/full

4. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022169422013440

5. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0158-3

6. https://www.wcrp-climate.org/decadal/rsmas_decadal/talks/Day2/Enfield_rsmas.pdf

7. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/features/will-hurricanes-change-world-warms

8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s003820000075

9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3945.1

10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027969

11. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abb0425

12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2006EO240001

13. https://weather.com/storms/hurricane/news/2025-10-27-category-5-hurricanes-atlantic-history-melissa